This brochure was produced for the Centennial Celebration of the Pelican Island

and the National Wildlife Refuge System. It is reproduced here with permission.

Photos of Pelican Island and "Let's Go" boat ©United States Fish & Wildlife Service (U.S.F.W.S.)

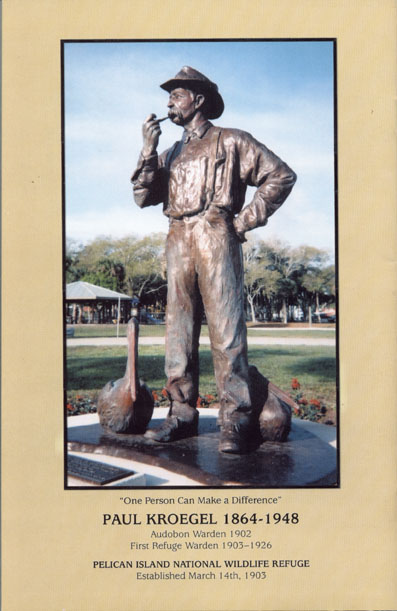

Photo of Paul Kroegel by George Nelson ©U.S.F.W.S.

Pelican Island NWR Stamp ©United States Postal Service

Photo of Paul Kroegel by George Nelson

Paul Kroegel on Pelican Island

One Person Can Make A Difference

A Story of Paul Kroegel and Pelican Island

March 2003

This commemorative publication was

first complied to celebrate the 90th

birthday of the Pelican Island National

Wildlife Refuge and to honor Paul

Kroegel, the Sebastian man, who

became its first warden. In 1963,

Pelican Island became a National

Historical Landmark. It is with great

pleasure that the Historical Societies

reprint and update this publication for

the 2003 Centennial Celebration.

Written by:

Arline Westfahl and George Keyes

Sebastian River Area Historical Society, Inc.

Edited by:

Ruth Stanbridge, County Historian

Indian River County Historical Society, Inc.

Sponsored by the Indian River County Tourist Development Council

THE KROEGEL HOMESTEAD

Take a trip back in time to the period just after the Civil War. The Sebastian area was low, swampy land between the St. Sebastian River and the Indian River. No roads existed and very few trails. There were alligators, poisonous snakes, and hordes of mosquitoes. Game was plentiful and fish abundant, but this area was a frontier, and frontier living was hard and often dangerous.

The 1860 census lists only two people, Andrew P. Canova and Ed Marr, living in this area. By the time of the 1880 census, about five households lived in the St. Sebastian River area, numbering less than 30 individuals.

To come to this area, one traveled by boat down the Indian River from a loading point at Titusville or Rockledge. Using this water highway, visitors saw a shore covered with thick woodlands and thousands of water birds. The land was flat, and the few inhabitants north of the Sebastian area had already planted citrus groves, as well as pineapples and crops, such as beans.

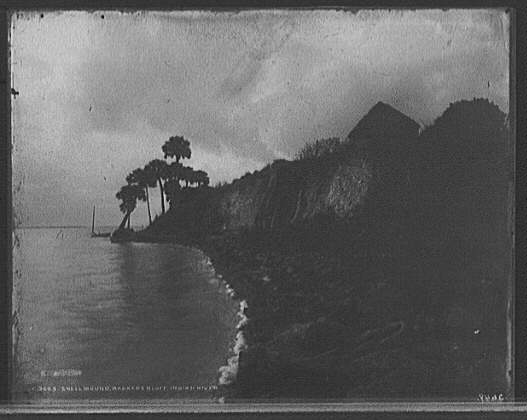

Imagine the surprise of such a traveler, sailing in his boat along this river highway, to suddenly see among the trees, a hill, a massive hill. In such a flat land, this must have been a startling sight. This hill, or bluff, caught August Park’s eye sometime after 1865, and, for a time, this German-born resident lived on it. His granddaughters, Mildred and Lenore Park, stated that their grandfather and fellow German, Gottlob Kroegel, became friends. Eventually, Gottlob Kroegel homesteaded the property surrounding this bluff, while August Park purchased other land in the area.

Jackson, William Henry, c. 1898, "Shell mound Barker's Bluff, Indian River",

Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

Kroegel homestead on Barker's Bluff, a huge "Ais" Indian Shell Mound.

By 1881, C.F. Gottlob Kroegel settled on that hill, a huge Ais Indian shell mound on the west bank of the Indian River in what was then Brevard County. He had come from Chemnitz, Germany, to the United States 10 years earlier, and settled first with his two young sons in Chicago. He left 12-year old Arthur Kroegel with a brother in Ohio, and brought 17-year old Paul with him to Florida. They came to the Sebastian area, which was called Newhaven in 1882 and changed to Sebastian in 1884. C.F. Gottlob Kroegel had heard of the Homestead Act of 1862.

The Homestead Act opened land to settlers with the provisions that five acres should be cleared and held for five consecutive years. A homestead was usually 160 acres; C.F. Gottlob Kroegel filed for his homestead, one of the first in the area, and was awarded the patent on June 21, 1889 and signed by President Benjamin Harrison. His land contained 143 and 18/100ths acres. The rest of the acreage was in the Indian River. It included Government Lots, 1,2,3, and 4 of Section 8, Township 31 South, Range 39 East and in order to acquire this land, he became an American citizen.

According to Frieda Kroegel Thompson, his granddaughter, "Gottlob first built a palmetto shanty, which was blown away by a hurricane a short time later; then he built a large frame house on top of the mound. The soil was rich on the mound and Gottlob raised winter vegetables mainly Valenti beans." He planted one of the first orange groves in the area and built one of the first packinghouses. The May 21, 1889 issue of The Indian River Advocate reported that, "Gottlob Kroegel made a shipment of 74 crates of beans. This is the largest number of beans shipped from here by one man". One old photo shows rows of plants on top of the shell mound where Gottlob had his house. These probably were bean plants.

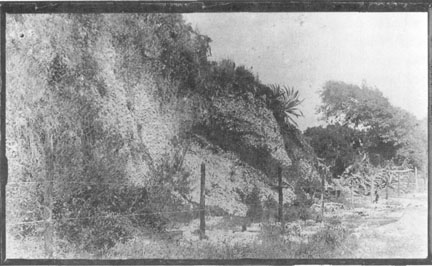

Photo courtesy of the Sebastian Area Historical Society

In 1908, a new house was built for Gottlob on the north side of the mound.

In 1908, Gottlob sold the shell mound to newly formed St. Lucie County for $4,000. A spur railroad was built from the railroad tracks on the ridge to the mound, and the shell was loaded and carried away to pave roads from Micco to Stuart. 1913 had leveled the ancient shell mound, with all the history of the ancient Ais Indians locked in it. In 1908, a new house was built for Gottlob Kroegel on the north side of the mound site, and, in 1910, he moved into this house. The old house was demolished. Gottlob Kroegel lived until 1923. Every Sunday throughout his life, his two sons, Paul and Arthur visited him and had a beer with him, according to Rodney Kroegel, his grandson.

Gradually over the years, portions of the homestead were sold off. One parcel went to the Jacksonville, St. Augustine, and Indian River Railroad, which later became the Florida East Coast Railroad. Another was sold when U.S. 1 cut through the homestead. Indian River Drive, once Dixie Highway, and once U.S. 1 also took some of the land.

A portion of the Kroegel Homestead is still held by the family today. The houses of Paul Kroegel and Frieda Kroegel Thompson, the 1913 garage, the packinghouse, and the honey house still sits in the hammock of live oaks at the end of Indian River Drive. The acreage where Rodney lived adjacent to his father’s 1899 house was purchased by Indian River County and will become a small park along a bikepath planned for Indian River Drive. Evidence of the Ais Indian mound, which once dominated the area, can still be seen.

Photo courtesy of Sebastian Area Historical Society

As a child, Rodney Kroegel rescued a variety of artifacts from the mound.

BARKER'S BLUFF, THE ANCIENT "AIS" INDIAN SHELL MOUND

The shell mound on the Kroegel homestead existed for thousands of years before modern history began in Florida. Prehistoric people, known as the Ais, or their predecessors, built this mound, as they did many others in the Indian River area. They left piles of shells and other refuse as the residue of the enormous amounts of shellfish they consumed. While many of these middens were low and sometimes continuous piles of shells, in certain places mountainous piles of shells were created. Possibly the mound offered a chance to spot their enemies more easily, or to view the ocean over the barrier island and to anticipate adverse weather conditions better. It is believe that it took many generations to produce such a large mound. They probably lived right on it as it was being constructed year after year.

Barker’s Bluff was one of the largest mounds in this part of Florida. It was reported to have covered more than five acres. Frieda Kroegel Thompson wrote, " The mound was 1,000 feet long, 400 feet wide at its widest point and higher than the tallest palm trees. …The shell mound dated back thousands of years B.C. and contained relics of campfires, pottery of many designs and ages, and bones of animals long extinct. …"

Photo courtesy of Sebastian Area Historical Society

Barker's Bluff was one of the largest midden mounds in this part of Florida.

Some pottery has been found and preserved over the years, and Rodney Kroegel rescued some artifacts from the mound when he was a child. He has a granite hatchet, pieces of pottery and six perfectly rounded, golf ball-sized coquina rock balls whose use is not known. He once had the skulls of a number of humans, but these have largely disintegrated. There was a small burial mound northwest of the large mound, which contained a number of complete burials. This area has been bulldozed over.

This history-filled mound, or midden, was given the name Barker’s Bluff after a John Barker, who was said to have lived on it. Legends about this John Barker have proved to be untrue, but the name continues.

On many early maps, the name of Two-Mile Bluff is also given to this site. As a landmark, this huge shell mound stood out along the low western edge of the Indian River and was used as a navigation aid. The early sailors may have considered it two miles from the St. Sebastian River, even though the actual mileage is more.

PAUL KROEGEL'S STORY

Paul Kroegel, and later his brother, Arthur, lived on the bluff with their father, Gottlob. They each had a grove of their own, Arthur, at the southern end of the homestead, where River Run Resort now stands. Paul’s was across the railroad tracks in a triangle of land near the western edge of the homestead.

Living on the bluff, Paul could always watch the river the birdlife on it, especially the pelicans, which were numerous. From the top of the bluff he could see Pelican Island, to the east in the Indian River, where the pelicans went to roost and nest. He came to love them.

Paul was a good carpenter, and became a boat builder. At age 21, after studying navigation, he earned his captain’s papers and was known as Captain Paul. He constructed a boat shop on the shore and built many of the early boats. He played his accordion at square dances up and down the coast as he traveled in his boats, the more famous of which were the Audubon, the 35-foot yacht, Irene, and the 50-foot schooner, Wanderer. This talented man also tended 100 beehives and sold honey and was from the "honey house" near his residence.

Photo courtesy of Sebastian Area Historical Society

Paul built a boat shop on the shore and created many of the early boats.

Paul’s love of the birds dominated this part of his life. He became increasingly disturbed by the plume hunters and the sportsmen on yachts who shot birds as they flew up when the boats went by. As these boats passed on the Indian River, the natural channel went quite close to Pelican Island, a five-acre island, home to thousands of pelicans. He often took to his sailboat and tried to discourage the shooting, but there were no laws, and no legal protection for the birds.

In 1902, Paul Kroegel was made game warden for the American Ornithologists’ Union. He began lobbying for the birds. He was aided by the Union, the Audubon Society; Dr. Frank Chapman, an ornithologist, who was fighting the plume hunters in other places; and a number of important people who wintered at Mrs. Latham’s Oak Lodge resort in Micco. She would keep Paul informed via the mail boat when someone was coming to visit who might help in the cause. The efforts of these people, spearheaded by Paul Kroegel’s dedicated work, finally paid off. President Theodore Roosevelt signed an Executive Order on March 14, 1903, creating the Pelican Island Reservation. On April 1, 1903, Paul Kroegel was appointed warden at a salary of $1 a month.

The Executive Order established the first National Wildlife Refuge in the United States, and Paul Kroegel became the first National Wildlife Warden.

During the last years of that campaign, Paul was leading a busy life. He built a house behind the bluff as a residence for himself and his new wife. He married Ila Lawson in October 1900.

After Paul assumed his place as warden, he was given a large flag to place on Pelican Island, but he put it on the bluff instead. Approaching boats blew their horns in respect when they saw the flag and that was a signal to him to get in his sailboat and place himself between the pleasure boats and the island, sometimes shooting off a gun to ward them off.

In 1901, George Nelson, a botanist, zoologist, photographer and lecturer, took the job of preparatore at the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology. Soon after that he began coming to Florida to study brown pelicans in the winter. He lived in Paul Kroegel’s house whenever he came, until Gottlob Kroegel sold him some land in 1910. His house still stands on the north end of the original Kroegel homestead in the Palmer Trailer Court. Young Rodney Kroegel often went on collecting trips with him when he was studying many kinds of wildlife. They went to the Fellsmere marshes and collected live moccasin snakes, turtles and other specimens. George Nelson taught Rodney and Paul photography skills. A large collection of George Nelson’s hand-painted glass slides of wildlife, especially pelicans and other birds belong to the Environmental Learning Center in Wabasso, Florida.

Paul Kroegel helped his son build a small building in 1916, which served as a darkroom. The building is on property that Paul eventually gave to Rodney when he married.

Paul also gave his daughter, Frieda, the land on which her house stands. This house is the house that was built for Gottlob Kroegel when he had to leave the mound. Frieda had it moved back to its present location, closer to that of her parents.

In 1899, when Paul’s brother, Arthur, married, Paul built his house. Arthur’s house was demolished to make room for a new house on the northern end of the original homestead property.

From 1905 to 1918, Paul Kroegel served as a St. Lucie county Commissioner. Paul and Ila had two children, Frieda and Rodney. Frieda died in 1989, Rodney in 1999. Rodney had been born in the same month and year, March 9, 1903, that the first national wildlife refuge was created, in a room on the second floor of the Paul Kroegel house. Paul lived until 1948, having been warden of the Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge until 1926, when the federal government discontinued the services of a warden.

Rodney told this story of this father. One night in 1910, Paul came into the bedroom that he and his sister shared, wakened them, and had them look out the window toward the east. They watched in awe as Halley’s Comet streaked across the sky and the Indian River Lagoon and the tiny little island of pelicans.

THE PELICAN ISLAND NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE

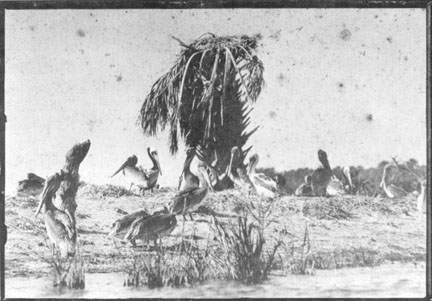

Pelican Island is currently a two-acre island along the east side of the Indian River, between Sebastian and Wabasso. Its fame as a bird rookery made it the center of controversy about a century ago as birds were wantonly destroyed. In 1903, it became the nations’ first National Wildlife Refuge as a result of an Executive Order by President Theodore Roosevelt. This beginning has now become a National Wildlife Refuge System of over 500 Refuges (540).

In 1911, when George Nelson published a study on Pelican Island, he wrote, "Many years ago it was well-covered with mangrove trees, in which the birds nested, but now only a few bleached stumps remain." After a hurricane in 1910, the river rose and completely covered the island. This forced the young pelicans to more elevated islands nearby. Birds then adapted to nesting on the ground instead of on the trees."

Photo from George Nelson Collection

Pelican Island has been a haven for brown pelicans for over 100 years.

In 1963, the refuge was increased to 616 acres, and, in 1968, another 403 acres were added. At present, it encompasses 4,359 acres of mangrove islands and bottom land in the Indian River, most of which are under lease from the State of Florida.

The future of the refuge and the sensitive lands in the Indian River has not always been secure. In 1918, members of the commercial fishing community charged that the pelicans were eating food fish and should not be protected. Children were placed on the island by the fishermen and told to kill the young in their nests. They bludgeoned 300 chicks to death.

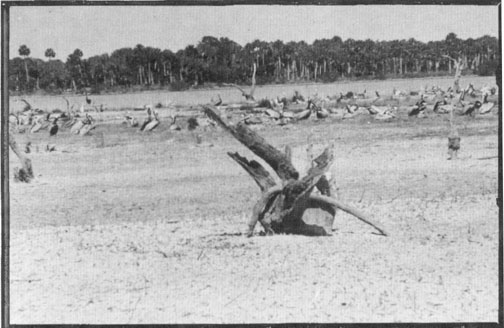

Photo from George Nelson Collection

Though it lacked vegetation for decades, the island's cover has now made a good comeback. Wave breaks, and new mangroves are also being added to stabilize the shoreline and help in the overall restoration process.

The Florida Audubon Society took a firm stand on this issue and invited an investigation by the Federal government. The Florida Federation of Women’s Clubs joined in this request. In the investigation some testimony was gathered. Mr. George N. Chamberlain of Daytona, Florida, wrote, "Previous to the advent of the Florida East Coast Railway, about 1890, fish were abundant in the Halifax and Indian Rivers, but with its coming began the fishing industry and immense shipments of fish northward were made at that time. .. The chief causes of largely diminished fish supply here and on the Gulf Coast are in my opinion mainly due to years of almost continuous seining."

B. J. Pacetti, Inspector Federal Bird Reservations, echoed this sentiment. He added, "it is a well-known fact that the pelican can catch only such fish as are on the surface of the water, and with one exception – the mullet – the food fish of Florida are … bottom fish and cannot be caught by the pelican." He went on to say that they fed their young mainly menhaden and other small, bony fish.

Photo from George Nelson Collection

During times without vegetation the pelicans learned to nest on the ground.

Warden Paul Kroegel wrote, "Regarding the reduced catches of fish, this is caused mainly the fishermen’s own greediness. There has been no law framed yet that the fishermen have not broken… The size of mesh in nets has been steadily reduced until now they are catching fish unfit for market, and unless something is done soon, the fishing business will be a thing of the past." That was 1918.

Photo from George Nelson Collection

The Island has weathered many stages of vegetation loss over the years.

INDIAN RIVER PRESERVATION LEAGUE

In 1963, Joe Michael, a prominent citrus grower, and other outstanding citizens, such as local fisherman Don Sembler found the Indian River Preservation League. They had become disturbed by the threat that bottomlands near the refuge would be filled in and converted to land for development. The Indian River Lagoon and its grassbeds were of vital importance as nursery areas for fish and other aquatic organisms. The policy of Florida’s Trustees of the Internal improvement Fund at that time was to sell these bottomlands for private development.

The Preservation League asked the State to change that policy and to enter into an agreement with the United States Fish and Wildlife Service to lease this area for the protection of Pelican Island and the Indian River Lagoon. Landowners directly east of Pelican Island who joined in this request were S.J. Pryor, George and Jeannette Lier, Thomas A. Vincent, Deerfield Groves, J.V. D’Albora, et al, and Helen J. Ryall. Many local civic organizations also lobbied the governor and cabinet. In a dramatic showdown in Tallahassee, this group of local citizens stopped the sale to the developer and changed the policies of the State of Florida concerning submerged land. The League moved forward to secure additional submerged acreage to enlarge this tiny little refuge and protect this rich estuary.

In 1963, Pelican Island was designated a National Historic Landmark and Sebastian hosted a commemoration ceremony. Various dignitaries attended to honor the nation’s first wildlife refuge and its first warden, Paul Kroegel. After this, the Indian River Preservation League quietly disbanded and another organization, the Pelican Island Audubon Society, was formed to become the conservation voice of Indian River County.

TODAY… TOMORROW … THE LEGACY by Ruth Stanbridge

Ten years ago when this little booklet was first printed Pelican Island and its surrounding waters had barely survived another attack from the rapid growth that was sweeping over Florida. Jungle Trail, an old public road meandering along Spratt’s Creek and east of the Refuge boundary, was the only buffer between development and the waters of the Refuge. A 37-acre parcel on the barrier island claimed by the Service was the subject of a 30-year old lawsuit with no immediate outcome in sight. Increased boat travel in the Lagoon was causing Pelican Island to slowly wash away.

Local citizens coordinating with a number of organizations and foundations and joined by Federal, State and local governments committed their energies and their resources to expanding, protecting, and restoring Pelican Island. The challenges were great and at times, the problems seemed insurmountable. By working together and moving forward the past ten years have produced success and a Centennial that will truly be a Celebration.

Today, the Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge has come into its own. Over 300 acres of new buffer lands on the barrier island have recently been acquired. Much of this land is the citrus land belonging to the pioneer families that rallied to save the Refuge in 1963. These groves will be restored to maritime hammocks and will protect Pelican Island and the surrounding waters from the impact of development. From the five-acre island of pelicans in 1903, the Refuge can now lay claim to 5,400 acres of habitat utilized by a multitude of species.

The old county road, Jungle Trail, is now designated a Florida Greenway and is a byway of the Indian River Lagoon National Scenic Highway. Soon it will be listed on the National Register as a Historical Site.

Through enhancement grants, Indian River County has constructed two facilities allowing visitors for the first time an opportunity to hike the trails and to see the birdlife of the first National Wildlife Refuge. One of these facilities is located on the 37-acre parcel of land that was once in litigation and now owned by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service.

On this parcel is also the Centennial Trail completed and ready to celebrate the great National Wildlife System by allowing a walk back in time to view Pelican Island as Paul Kroegel did a hundred years ago from his shell mound across the river.

The Kennedy family sponsored the first printing of this booklet in 1993 for the 90th Celebration and Sue Kennedy Holbrook penned the following lines.

"The story of the preservation of Pelican Island is the story of commitment… ".

Today, as we enter the next century, new commitments must be made as we continue the protection and preservation of our natural and historic resources. The legacy we must leave is one person can make a difference.

Paul Kroegel made a difference, so did President Theodore Roosevelt, so did Joe Michael.

So can you!

Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge Commemorative Stamp

The United State Postal Service issued a Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge commemorative stamp on March 14, 2003 to honor the Centennial Celebration of the National Wildlife Refuge system of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The stamp features a photograph of a brown pelican by Dr. James Brandt. Pelican Island first garnered national attention in the early 1900s as the last breeding ground for brown pelicans on the east coast of Florida. It was this national attention that led President Theodore Roosevelt to establish Pelican Island as the first official national wildlife refuge in the United States.

The commemorative stamp is a 37-cent First Class stamp with text at the bottom which read "Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge 1903-2003." The issuance of this stamp by the U.S. Postal Service signifies the importance of this event in American history.

Carl T. Herrman is the art director for the commemorative Pelican Island stamp and had been an Art Director for the U.S. Postal Service since 1992.

For more information on commemorative stamps and the U.S. Postal Service, go to www.usps.com

Photo courtesy Indian River County Historical Society