(The following article was published in the February 2003 issue of the "Vero Beach Magazine".

It is reprinted here with permission of the Vero Beach Magazine™ - www.verobeachmagazine.com)

THE NATION’S FIRST WILDLIFE REFUGE CELEBRATES ITS CENTENNIAL

PELICAN ISLAND –

100 YEARS IN THE MAKING

By ERICK GILL

President Theodore Roosevelt

There is a clock in Paul Tritaik‘s office that counts down the days, hours, minutes and seconds until March 13. Even though the electronic counter was installed a few months ago, it is a countdown that has been ticking for more than 100 years.

Tritaik is the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Refuge Manager for Pelican Island – a 2.5-acre piece of land that rests in the Indian River Lagoon just north of Windsor between the Sebastian Inlet and the Wabasso Causeway. This March marks the Centennial Celebration of the first National Wildlife Refuge created by President Theodore Roosevelt on March 13, 1903.

"What he started has really grown into the world’s largest system of lands dedicated to the conservation of wildlife," says Tritaik, just 70 days, nine hours, 25 minutes and 15 seconds away from the Centennial Celebration. "Part of what we are trying to get across is not only that Pelican Island is celebrating its 100th anniversary, but the whole National Wildlife Refuge System is."

"WILD BEASTS AND BIRDS ARE BY RIGHT NOT THE PROPERTY

MERELY OF THE PEOPLE WHO ARE ALIVE TODAY, BUT THE PROPERTY OF UNKNOWN GENERATIONS, WHOSE BELONGINGS WE HAVE NO RIGHT TO SQUANDER."

— PRESIDENT THEODORE ROOSEVELT

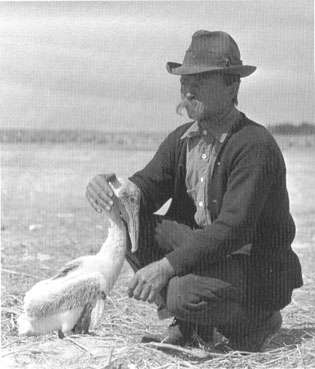

America's first game warden and wildlife manager,

Sebastian resident Paul Kroegel (1864-1948) with a

brown pelican at Pelican Island taken in 1907.

Pelican eggs rest in a nest on Pelican Island, home to more than 90 species of birds.

That "system" includes 535 Wildlife Refuges containing more than 95 million acres. There is at least one in every state, and one within at least an hour’s drive of every major U.S. city. The Wildlife Refuges are home to more than 700 species of birds, 220 species of mammals, 250 reptile and amphibian species and more than 200 types of fish. Many of those creatures seek shelter in the refuges. There are more than 250 threatened or endangered plants and animals living there, including manatees, bald eagles and the California jewelflower.

Sitting in his office talking about Pelican Island and the upcoming celebration, Tritaik sounds more like a historian than a refuge manager. He namedrops important community environmental leaders from the early ‘60s. He can rattle off the names of presidents who played an important part in the National Wildlife Refuge System: both Roosevelts and Carter. He can even explain the funding for the refuge system, dating hack to the Duck Stamp in 1958. Tritaik is a fountain of knowledge, but the well runs deep when it comes to Pelican Island.

An aerial view of Pelican Island, which sits in the Indian River between the Sebastian Inlet and the Wabasso Causeway. The 2.5-acre island is birthplace of the National Wildlife Refuge System,

"It’s remarkable to think about all the firsts Pelican Island has been involved in," he says. He explains that the island was not only the first Wildlife Refuge, but the site of one of the first environmental education programs. Furthermore, it was the first area where the state canceled the sale of wetlands to developers.

However, all of that wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for a bird-loving Sebastian resident named Paul Kroegel.

BACK TO WHERE IT ALL BEGAN

During the late 1800s a small group of Americans were beginning to see a lot of the wildlife disappearing. The "wild west" was invading the wildlife. The bison were close to extinction. The Carolina parakeet and passenger pigeon were wiped out. In Florida, many water birds including pelicans, spoonbills and egrets were shot and killed for their feathers. It was recorded that as many as 60 roseate spoonbills were gunned down per day. Plume feathers, used in the fashion industry to decorate women’s hats, were sold on the market for sometimes twice the rate of gold.

Paul Kroegel and George Nelson protected wildlife in the Indian River during the early part of the 1900s.

The feather trade led to the serious decline of many species of wading birds, especially in Florida. By the end of the 19th century, many hunters and egg collectors found out about Pelican Island. At the time, the island covered 5.5 acres in the Indian River and as many as 5,000 brown pelicans could be found nesting there.

Because of the statewide slaughter of birds, Pelican Island became the last rookery for brown pelicans on the east coast of Florida. Kroegel, a German immigrant who lived on an Ais Indian shell mound on the west hank of the river, took a special interest in protecting the birds. His home overlooked Pelican Island and with his boat and a 10-gauge shotgun he tried his best to protect the wildlife from poachers. By doing so, he unknowingly became involved in the "feather wars," the stand-off between plume hunters and conservationists.

Kroegel soon incorporated the help of well-known naturalists such as Frank Chapman, a member of the American Ornithologists’ Union and the eventual Curator of the Birds at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. With some pressure from the American Ornithologist’s Union and the Florida Audubon Society, several laws were passed to protect non-game birds. The first federal law was the Lacey Act in 1900, which made it illegal to sell protected birds across state lines. The following year, Florida passed the first non-game bird law. Shortly after, Kroegel was commissioned as one of four Audubon wardens to protect the remaining water birds. Two of those wardens were killed in the line of duty.

By 1903, without major media coverage or national celebration, President Theodore Roosevelt signed an executive order establishing Pelican Island as a federal bird reservation — the first step in what would become the National Wildlife Refuge System. It was the first time the federal government had set aside land for the protection of wildlife. As the first National Wildlife Refuge Manager, Kroegel earned $1 a month from the Audubon Society, since there were no funds set aside by the government for this position. So with just a badge, a boat and a shotgun, Paul Kroegel guarded Pelican Island and its residents until 1926. President Roosevelt went on to create 54 more National Wildlife Refuges during his two terms in office.

During the "Feather Wars" many species of birds were close to extinction, being killed for their feathers, which were used in expensive hats. As many as 60 roseate spoonbills were killed per day on Pelican Island during the early part of the century.

"It was good that we had such a bold president at that time because that’s what we needed," Tritaik says.

While the threat of plume hunters died down in the first part of the 20th century, Pelican Island soon came under attack by commercial fishermen, who feared the birds were eating into their profits. This battle reached a climax in the spring of 1918, when more than 400 pelican chicks were clubbed to death on the island. The Florida Audubon Society again came to the rescue, proving that the pelican’s primary diet consisted of non-commercial baitfish. By the mid-1900s, after years of protection, most of the species of water birds returned to the island.

A new menace emerged in the 1960s. Investors were trying to convince the state to sell surrounding wetlands and islands for development. However, the state actually reversed its decision to unload the wetlands thanks to a group of residents. In 1963, local citrus growers, commercial fishermen, sportsmen and residents joined forces as the Indian River Area Preservation League and were able to convince the state to include 422 acres of mangrove islands as part of the refuge. Five years later, the state added another 4,760 acres.

CONTINUING A TRADITION

Despite the fact that Pelican Island was the first National Wildlife Refuge, it didn’t receive an annual budget from the federal government until two years ago – 98 years after it was created.

Paul Tritaik became the refuge manager 10 years ago. He recently was able to hire a staff of six to help manage Pelican Island, which has grown to incorporate more than 5,000 acres, as well as the Archie Cart National Wildlife Refuge, which totals about 900 acres north and south of the Sebastian Inlet.

Besides Tritaik and Kroegel, the only other Pelican Island Refuge Manager was Lawrence Wineland, who looked after the land from 1964-1981.

"He was somewhat of a pioneer himself," says Tritaik.

Wineland made environmental education a big part of his job, often using his own boat to take elementary school kids out to the island, teaching the history and environmental significance of the Indian River Lagoon.

"And this was in the ‘60s and ‘70s when environmental education wasn’t as popular as it is today," Tritaik adds.

For the first eight years on the job, Tritaik was the one person to look after the refuge and he no longer had to run plume hunters off Pelican Island with a shotgun. Instead, he monitored sea turtle nests along the beaches in the Archie Cart Refuge. He was responsible for additional land acquisitions that provided better buffers around the refuge from encroaching development. He removed exotic vegetation such as Brazilian pep-pets and Australian pines.

Most of all, he has looked after the animals. There are more than 90 species of birds in the refuge, including brown and white pelicans, wood storks, roseate spoonbills and various herons and egrets. Recent surveys tallied as many as 97 pelican nests and 146 wood stork nests. Other wildlife includes manatees, endangered sea turtles such as the green and loggerhead, rabbits, raccoons and otters.

"The wildlife out there is what makes it so special to me," he says. "This is a small area that is in a growing community, and to see bobcats, indigo snakes, wood rats, beach mice, wood ducks to know we re protecting a little piece of landscape for the critters – is what makes it special for me.

"Most people don’t get excited about rodents, but to me they’re all special," Tritaik says.

That’s the biggest difference between National Wildlife Refuges and National Parks, explains Tritaik. The National Wildlife Refuge System was created to protect the animals living within and around the refuge, whereas the National Parks are public-use lands that focus on protecting the natural environment. While 98 percent of the Wildlife Refuges are open to the public for hunting, fishing and hiking, Tritaik says, most refuge systems start out closed to the public. Even though the Wildlife Refuge System may not get the attention that the national parks get, it is estimated that more than 40 million people visit them each year.

One of the toughest challenges in managing Pelican Island is protecting it from erosion. During the last 40 years, the island’s land mass has shrunk by half, decreasing from 5.5 acres to 2.5. Some of the erosion can he blamed on storms and natural tidal flows, hut most of it is due to boat wakes. The government has tried to prevent further erosion by adding 250 tons of oyster shells to build a protective harrier between the island and the waves.

OPENING THE GATES

Planning for the opening of Pelican Island began around 1994. Even though the refuge had long been established and Pelican Island was already in place, there was no public entrance into the refuge. The only way to really see the island was by boat. In the mid ‘90s, Tritaik began to get opinions from those in the community as to what they would like to see at the refuge. He heard opinions from all sorts of community groups on what U.S. Fish and Wildlife should and shouldn’t do.

"It was a collaborative effort. We really tried to reach out to the community beforehand to see what they wanted," he says. "The finished product is going to be very basic and unobtrusive. Something everybody can agree on.

"We’ve gotten a lot of support from the community and this wouldn’t have happened without it."

A lot of the imagination and planning that has taken place since 1994 has turned into a reality in the last six to eight months.

"Nothing has been easy," Tritaik says, "hut it’s certainly been worthwhile."

Joanna Taylor, refuge ranger, has spent the last few months giving exclusive tours to reporters from travel magazines and wildlife and outdoor publications. The 100th anniversary has garnered a lot of media interest. ESPN is planning to air several outdoors shows set in the refuge and there is even talk of President George W. Bush attending the ceremony.

"Hopefully this will help people grasp and understand the enormity of the wildlife system," Taylor says as she climbs the Centennial Trail Boardwalk. "This is the place where the National Wildlife Refuge movement took foot."

The meandering Centennial Trail Boardwalk is the cornerstone of the Pelican Island refuge. It is an elevated path that wanders through a tidal mangrove swamp and hammock habitat and ends at an 18-foot-tall observation tower that will give the public its first land-based view of Pelican Island. The observation tower, conceived by Wineland in 1963, incorporates more than 530 engraved planks — one for each refuge in the system spaced throughout the length of the boardwalk. The trail will also feature interpretive panels that focus on the entire Wildlife Refuge system.

"It’s hard for people to appreciate the scope of what happened here without seeing it," Taylor says.

The public will access Pelican Island off of AlA onto Jungle Trail. Once the Centennial Celebration is over, the park will he open free to the public on a daily basis from dawn to dusk. The one-to two-year project will feature a 3.5-mile walking trail "that is great for bird watching" and a 1.5-mile wildlife drive — an unpaved ecofriendly roadway through the refuge. Though there are no plans to provide boat ramps or camping, fishing will he permitted.

If Pelican Island is such a sensitive area, some people may ask, why disturb it? According to Tritaik, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services aren’t disturbing anything. They’re repairing the area. Most of the land around Pelican Island was turned into citrus groves, which aren’t conducive to sustaining birds and other wildlife. So the government has been trying to reverse the hands of man by creating fresh water ponds, palm prairies, tidal marshes and mangrove forests and by removing citrus trees and Australian pines.

"We’re trying to restore the land to its natural habitat," says Taylor, adding that she recently saw an otter take up residence in one of the new ponds. Tritaik also sighted an alligator in the refuge for the first time this past summer.

"We want to bring the ‘Jungle’ hack to Jungle Trail," he says.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services will get assistance from Indian River County on the installation and upkeep of some of the public facilities. Tritaik hopes in the future to have a full-time wildlife officer assigned to the refuge. He also envisions an army of volunteers who, along with help from the Environmental Learning Center, will lead tours and educational trips through the refuge.

And as the clock in Tritaik’s office keeps ticking away until March 13, he knows how important time really is.

"Hopefully, what we do today will benefit future generations, just like what Paul Kroegel and President Roosevelt did 100 years ago."